In Georgia, the 1990s started with the collapse of the USSR and went on with the civil war, ethnic conflicts, and losing control over some territories, followed by the economic, humanitarian, and political crises. The early XX c. they highlighted with legislative changes and the emergence of a particular culture. The Georgian theatre of the time was plagued with an economic crisis and needed urgent structural and operational renovation. In this regard, many people turned their gaze at the new generation directors, who would hopefully define the Georgian theatre in the times to come. Vasil Kiknadze, the theatrical critic, wrote: “A new wave of directors, who have made some forward-looking statements, is gradually gaining ground. It’s not an overstatement to say that the contemporary Georgian theatrical productions and artistry can stand up to the international competition “[1]. We can certainly agree with the critics’ assessment, but the essential operation of the theatres and their adequacy to the processes underway across the world is another matter.

The Basement Theatre opened in 1997 started working supported by grants and, also, its revenues. It proved that a Georgian theatre could operate without the State subsidies, which was against a widespread opinion that culture is not profitable and no place for making money. The “Basement” pushed forward the art of the theatre. A new generation of directors and playwrights endeavoured to make a mark in the hard times.

In this publication, I’d like to speak about David Sakvarelidze, a representative of that generation, who is now a well-known theatrical director and who was one of the first to realise and speak out about the necessity of the structural renovation of the theatre for he believed that without it, the theatre had no future. “The Times” newspaper said about him in one of its issues of 1998: “At 28, Sakvarelidze is already the godfather of an emerging generation of artists, who are eager to look further afield. Sakvarelidze has amassed a vast library of texts and tapped performances of everyone from Robert Wilson to Edward Bond.” In the same article by Hettie Judah, Sakvarelidze says: “You cannot make a good theatre within a governmental structure. I work in underground theatres because I prefer to be free... “[2]

Initially, he introduced himself to the public as a talented theatrical composer (David Sakvarelidze is one of the most exciting and gifted composers of the Georgian theatre today –David Bukhrikidze[3]). However, he soon showed his potential as a theatrical director. In the early years of this century, the dramatic critics described him as a postmodernist director (“David Sakvarelidze’s new play “The Agape” heralded the post-totalitarian age at the Rustaveli Theatre” - David Bukhrikidze[4]). This experimenter knew how to manage the theatre (“Sakvarelidze’s style, a kind of lightness and irony are the indications of the new trends in the Georgian theatrical art” - Lela Ochiauri[5]). His potential of the theatre manager revealed itself in the implemented projects and festivals we are going to speak about below.

The borders opened, and enormous flow of information became accessible to the young Georgian artists. It was at the time that the “Basement” started its search for a new theatrical language. The political theatre so well known to the Georgian theatregoers went to the background giving way to the op-ed, documental genre. Together with a group of like-minded artists, David Sakvarelidze sets up the Caucasian Theatre Lab, quite a few international and local projects and festivals were conceived. In cooperation with the “Basement Theatre”, the Laboratory established at the Royal District Theatre introduces a new trend. The plays by the new generation playwrights attract attention. It was at the time that David Sakvarelidze and Lasha Bugadze, the playwright, started working together. “Otari”, a comedy by the 19-year-old playwright depicts the paradoxes of our daily life and the absurdity of the Georgian family routine. In the piece, the family members eat up one another, Otar’s son marries a cow, while his wife devours his mother to bear and raise her again. The play staged at the “Basement” in 1998 had a positive critical and public response. The State-subsidized Georgian theatres also turned to the new generation playwrights. The Sakvarelidze-Bughadze duet was invited to Kote Marjanishvili Theatre, wherein 1999, they put on “Doctor Frankenstein.” Meanwhile, the director-playwright collaboration had been a long-established international practice. The Georgian production of “Frankenstein” roused public interest and the walking dead was much talked about in the capital Tbilisi. The audience witnessed the level of cruelty they had not been accustomed to: a corpse strangles a child, rapes a woman and kills Matheus, the village abbot. In the early 90s, when a new “in-yer-face theatre” drama style emerged, such scenes seemed shocking even at the British theatre. “Aleks Sierz, the theatrical critic used the term as the title of his book “In-yer-face Theatre – the British Drama Today” first published in 2001. In it, he described the pieces by the young playwrights, who showed shocking and confrontational scenes. In his view, Sarah Kane, Mark Ravenhill and Anthony Neilson were the most noteworthy representatives of the style, who fought against the social cruelty with likewise “cruel” methods.”[6]However, the scenes of the tragicomedy did not stir the audience’s negative response, maybe because, over the last decade, the people witnessed cruelty likewise in the streets of Tbilisi daily. It is evident that by “Doctor Frankenstein” the Georgian theatre tried to keep up with the British theatre, an accurate benchmark.

David Sakvarelidze is no stranger to the world and particularly so, the British theatre. In 2001, he was one of the young artists chosen by Peter Brook, the legendary theatre director, to work with him at the London National Theatre Studio. But it is not only for his association with the great Peter Brook that his artistic biography is impressive. He did master classes with Luca Ronconi, Richard Schechner, Mikheil Tumanishvilito and Robert Sturua. He studied at the NYU „Tisch School of the Arts”, staged a play at “Play-Time Studio”, had a study placement at New-York’s “New York Theatre Workshop”.

Cruelty is also the topic of his plays based on the pieces by Edward Bond and Hanoch Levin. In 1998, he introduces the Georgian audiences to “Park”, the play by Botho Strauss, the contemporary classic German playwright. Staged at the Royal District Theatre in Tbilisi, the piece joined several other sponsored experimental productions. Similarly, as 20 years ago, David Sakvarelidze says that in order to survive, the Georgian theatre must be independent and free.

The Caucasian Theatre Lab founded by David Sakvarelidze, aimed at staging the plays by the new generation Georgian, and in broader terms, Caucasian playwrights. He initiated the entry of pieces by Lasha Bugadze and Manana Doiashvili for “The Festival of Young Playwrights” in Moscow, a kind of a springboard for their production at Moscow’s renowned Moscow Art Theatre. “A Woman on a Tree,” the experimental piece by Jarji Akimidze and David Turashvili, was also put on at the “Laboratory” by David Sakvarelidze. The director singles out the play as especially important to him for it deals with the problems a woman, the family and the Georgian society faced. Then came “This Chair and that Bed” by Lasha Bugadze and many other op-ed genres play by the Georgian playwrights.

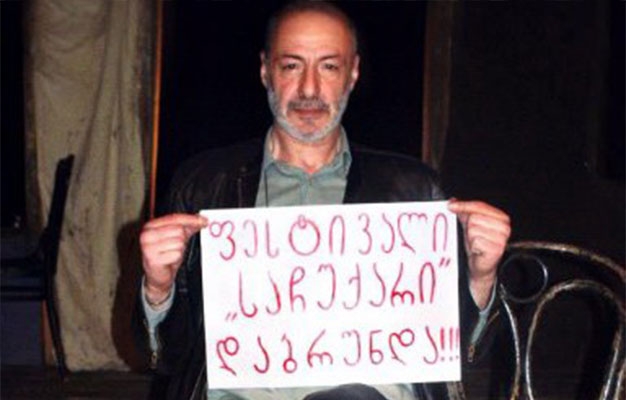

The International “Small, Small, Small” moving the theatrical festival, involving companies from 33 countries, which visited all the hot spots in the Balkans and South Caucasus was the most outstanding “Laboratory” project. The Festival hosted by the Georgian Marjanishvili Theatre was a kind of a campaign undertaken by the war-stricken countries. Opened in Tbilisi, the festival went to several European and Asian cities to finally close in Paris.

With this, we finish this publication, which touched upon the developments at the Georgian theatre some 20 years ago. We believe that we did the right thing to show that the creation of a new theatre is not only about the creative potential. Unfortunately, even today, two decades later, a structural renewal of the theatre is still a hot issue.

[1]V. Kiknadze, Spring of the Theatrical Season – The Stage Revival, “The Republic of Georgia” newspaper, 1996.

[2]Judah H., New Waves on the Black Sea, THE TIMES, 1998.

[3]D. Bukhrikidze, Theatre in the Age of Bullets, “7 Days” weekly newspaper, 1996.

[4]D. Bukhrikidze, Theatre in the Age of Bullets, “7 Days” weekly newspaper, 1996.

[5]L. Ochiauri, This is a Hell of a City where Cruelty is the Ruler, “Resonance” newspaper, 1997

[6]A. Kvinikadze, The British Theatre of the ’90s and The Plays by the Contemporary British Female Playwrights, 2018. Available at: http://georgiantheatre.ge/441-90-iani-tslebis-britanuli-theatri-da-thanamedrove-britanel-qaltha-dramaturgia.html

The forthcoming seminar for Georgian young theatre critics

25-March-2015, 10:17

Phantoms

15-December-2013, 23:24

Festival, festival…

09-November-2013, 13:51